Your Rights and Responsibilities

As a member of the UWRF community, you're an equal and active participant in both understanding the history of and being part of the future of the promotion and advancement of free speech, freedom of expression and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

What's Our Goal?

This page is designed to highlight information about free speech and the freedom of expression, UWRF's commitment to upholding these rights and our desire to create a community that both upholds the First Amendment and prioritizes diversity and equity efforts, which can at times seem to be at odds. Explore this page to find answers to frequently asked questions about free speech and to discover your rights and responsibilities as a member of a public university.

Rights and Responsibilities

While opinions and viewpoints may vary, everyone plays a role in the promotion of freedom of expression. Explore below for some basics on how you fit into the equation.

What does academic freedom look like in the classroom?

Faculty are able to "discuss and present scholarly opinions and conclusions on all matters both in and outside the classroom" and that speech/expression is protected. Specifically, academic freedom covers teaching, research, intramural speech and extramural speech. Academic freedom protects opinions, popular or not, that aim at getting to the truth specifically related to the subject matter at hand.

For more information, please view our Resource Guide for Academic Freedom, Political Activity and Records Requests.

How can you promote and engage in freedom of speech and diversity of thought within the classroom?

- Share your opinions with your classmates and within the class.

- Come from a place of curiosity, compassion and respect when you are engaging in dialogue where there is a difference in opinion.

- Abide by the expectations outlined in the class syllabus.

- If there are concerns about disruption to the class, document this behavior and communicate with the involved students and/or instructor.

What is the difference between academic freedom and free speech?

Academic freedom doesn't provide the same level of protections as the First Amendment, which protects individual free speech rights. Academic freedom is a recognized principle in higher education and typically is related to the subject matter being taught or researched. It's important to state that there is not a body of case law that supports academic freedom like there exists for the First Amendment.

Participation in freedom of speech

As a public university student, you have the right to express yourself freely. This can be through many avenues, including but not limited to the way you speak, the organizations you join, the protests you participate in and more. While it can be nerve-wracking to share your opinions in different settings, it is your right to express yourself freely.

It is important to know that there are generally three different environments to consider when expressing your First Amendment rights and each of these environments do not have the same level of First Amendment protection. The first is a traditional public forum, such as a public sidewalk. This is an environment where you can express your free speech with a higher level of First Amendment protection. The second is a limited public forum, such as a student union, where you may not have the same level of protections. The third forum is a non-public forum, such as a classroom during class time or an office space, which has the potential to limit your speech.

We also believe that you have a responsibility to express yourself in ways that share your opinions and allow you to learn about other opinions. This requires you to engage civilly and respectfully with others. By doing so, you will gain new insights and different perspectives that you might not have otherwise have gained.

By approaching freedom of expression in this way, we don’t expect you to always agree with another person. In fact, we acknowledge you likely won't in some circumstances. However, we believe taking this approach will encourage you and your peers to engage in conversations that challenge one another and expand your understanding of others’ perspectives, beliefs and worldviews.

The responsibility of civil discourse

When you want to engage in any dialogue, it is imperative to approach conversations with respect and curiosity. In short, that is civil discourse, which is explained in length below.

Civil Discourse

Understanding civil discourse is crucial to creating an environment that promotes and supports freedom of expression.

A few keys to civil discourse:

- Be mindful of your own behavior. This means paying attention to how your words (and your silence!), your tone, your facial expressions and your body language impact others in the conversation.

- Wait your turn. Don't interrupt or speak over someone who is already speaking. Pausing before speaking also gives you time to fully hear what the other party is saying

- Ask questions. Don't assume intentions or that you know what the other person(s) means. It's okay to ask questions! This gives you an opportunity to understand other perspectives.

- Separate fact from opinion. Facts and opinions can both be valid but it's important to know and understand the distinction.

- Find common ground. Finding an area of agreement, no matter how small, can help you connect with others.

- Be respectful. Don't demean others with your language, stay engaged and be considerate.

Debate versus discussion

Goal: The goal of a debate is to win, while the goal of a discussion is to learn and grow. In a debate, participants are trying to prove their point of view is correct, while in a discussion, participants are trying to understand all sides of an issue.

Structure: Debates are more structured than discussions. Formal debate formats usually have a moderator who keeps the debate on track and ensures that both sides have a chance to speak. Discussions are less structured and more free flowing.

Rules: Debates have a set of rules that participants must follow. These rules typically include things like not interrupting other speakers, staying on topic and providing evidence to support your claims. Discussions do not have as many rules. Participants can speak freely and share their opinions, even if they are not always well-supported.

Attitude: Debaters are typically more adversarial than discussants. They are trying to win the debate, so they may be more aggressive in presenting their arguments and challenging the arguments of the other side. Discussion participants are more collaborative. They are engaged in the process to learn and grow, so they are more open to hearing different perspectives and changing their minds.

In general, debates are more formal and competitive than discussions. They are an effective way to test your knowledge and sharpen your argumentation skills. Discussions are more informal and collaborative. They are a good way to learn about different perspectives and come to a better understanding of an issue.

Curiosity and empathy mitigates discomfort in disagreement

Curiosity and empathy can help students mitigate discomfort in disagreement in a few ways:

- Curiosity can help students see the other person's perspective. When we are curious about someone else's point of view, we are more likely to try to understand it, even if we do not agree with it. This can help to reduce the feeling of discomfort that comes from disagreement, as we no longer see the other person as an adversary.

- Empathy can help students connect with the other person's feelings. When we empathize with someone, we try to understand and share their feelings. This can help us to see the disagreement from their perspective and to feel compassion for them. This can make it easier to have a productive conversation about the disagreement.

- Both curiosity and empathy can help students to see disagreement as an opportunity for learning. When we are curious about someone else's perspective, we are more likely to be open to learning new things. This can be a valuable experience, as it can help us to grow and develop our own thinking. Empathy can also help us to see disagreement as an opportunity to connect with others and to build relationships.

In addition to these specific ways, curiosity and empathy can also help students to overcome discomfort in disagreement in general by creating a more positive and productive learning environment. When students feel safe and respected, they are more likely to be open to different perspectives and to engage in meaningful dialogue. Curiosity and empathy can help to build this type of environment by promoting understanding and compassion.

Here are some strategies that can used to help demonstrate curiosity and empathy:

- Ask open-ended questions that encourage students to think critically and explore different perspectives.

- Provide opportunities for students to learn about diverse cultures and viewpoints.

- Model curiosity and empathy by being open to innovative ideas and by listening to others with respect.

- Create a classroom climate where students feel safe to express their opinions, even if they are different from the majority.

Consequences of ideas

Engaging in argument rather than discussion or debate can be counterproductive.

- Misunderstandings. When we do not take the time to think about what we are saying, we can easily misunderstand each other. This can lead to arguments and conflict.

- Inaccuracy. When we do not have all the facts, we are more likely to say things that are inaccurate or misleading. This can damage our credibility and make it difficult to have productive conversations.

- Emotional reactions. When we speak without thinking, we are more likely to let our emotions get the best of us. This can lead to intense arguments and unproductive discussions.

By taking the time to have well-reasoned and informed discussions, we can avoid these pitfalls and create a more positive and productive environment for everyone.

Here are some tips for having discussions:

- Do your research. Before you participate in a discussion, take some time to learn about the topic. This will help you to form a more informed opinion and to avoid saying something that is inaccurate or misleading.

- Be respectful. Even if you disagree with someone, it is important to be respectful of their opinion. Avoid name-calling, insults, and other forms of personal attacks.

- Listen actively. When someone is speaking, really listen to what they have to say. Do not just wait for your turn to talk.

- Ask questions. If you do not understand something, ask questions. This will help you to clarify your understanding and to learn more about the topic.

- Be open to changing your mind. If you are presented with new information that challenges your beliefs, be open to changing your mind. This shows that you are willing to learn and grow.

By following these tips, you can have thoughtful discussions that are productive and beneficial for everyone involved.

The Wisconsin Idea

The Wisconsin Idea is a philosophy that states that the University of Wisconsin System should extend its services and resources beyond the university's boundaries to serve the people of Wisconsin. This includes a commitment to academic freedom and freedom of expression.

Academic freedom is the freedom of faculty members to teach, research, and publish without fear of censorship or reprisal. Freedom of expression is the right of all members of the Falcon Family to express their ideas, even if those ideas are unpopular or controversial.

UWRF is committed to these principles. The UWRF Student Handbook states that "all members of the university community have the right to freedom of expression, including the right to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn." The handbook also states that "the university will not restrict freedom of expression unless such restriction is necessary to protect the rights of others or to preserve the orderly functioning of the university." More information is available in the Student Handbook.

In practice, this means that students at UWRF are free to express their ideas in the classroom, in the residence halls, on social media and in other public forums. However, the level of First Amendment protections is not the same in all of these environments. For example, students cannot express their ideas in ways that are threatening or harassing, or that disrupt the university's orderly functioning. Additionally, during class time, a classroom is generally not a public forum and a professor can limit speech in the classroom that could not be restricted in a true public forum, like a city block.

Here are some examples of how the Wisconsin Idea and freedom of expression directly connect to our campus:

- The university offers courses exploring controversial topics such as race, gender, and politics.

- Students are encouraged to participate in student government and other organizations where they can voice their opinions on issues that matter to them.

- The university hosts various events, such as lectures, debates, and film screenings, that provide a forum for discussing controversial ideas.

- The university's library and media center offer a wide range of resources that students can use to learn more about different viewpoints.

The principles of the Wisconsin Idea and freedom of expression are essential components of the larger mission of UWRF. These principles allow opportunities for students to explore new ideas, challenge their assumptions, and develop the critical thinking skills they need to be engaged citizens.

Our Resources

Have more detailed questions or need clarification? Email deanofstudents@uwrf.edu to learn more.

Report It!

UWRF values a diverse community where all students, faculty and staff are able to fully participate in the campus community. We encourage reporting so that we can appropriately and promptly address any concerns. Please review the options for reporting and don't hesitate to reach out!

The Report It! Page allows students, faculty and staff to report concerns about hate/bias, sexual misconduct and other concerning behavior happening on campus.

Community Concerns Response Team

UWRF is dedicated to fostering an inclusive community. The Community Concerns Response Team (CCRT) serves the campus community by collecting reports of hate and bias on campus and responding to them using the appropriate mechanism.

If you or someone you know has experienced a form of hate or bias within the UWRF campus community, you can file a report using our Report It! process. It is important to note that offensive comments are most often protected by the First Amendment. Reporting a hate/bias incident does not typically result in disciplinary action. However, reporting these incidents is important for us to document and could result in the CCRT reaching out to impacted parties to provide support. There are also opportunities for students who use their First Amendment rights that result in a hate/bias incident to have educational conversations that are not disciplinary in nature.

Counseling Services

Counseling Services provides on campus professional mental health services to UWRF students. Services are short-term and the office can assist with referrals to mental health professionals for long-term mental health support.

Student Inclusion and Belonging

The Student Inclusion and Belonging Center at UWRF strives to create an inclusive campus community where all people can feel valued, respected and safe. As such, the center is dedicated to affirming and embracing the multiple identities, values, belief systems and cultural practices of the campus community. We foster student learning through inclusive and empowering experiences in the areas of identity development, multicultural awareness, leadership workshops, campus outreach and campus activities.

Dean of Students Office

The Dean of Students Office promotes student awareness and an understanding of their rights and responsibilities as university community members through:

- Addressing student conduct issues

- Creating developmental learning opportunities

- Engaging students in ethical decision-making

Related policies

- Discrimination, Harassment and Retaliation: "It is the policy of UW-River Falls to maintain an academic and work environment free of discrimination, discriminatory harassment or retaliation for all students and employees. Discrimination is inconsistent with the efforts of UW-River Falls to foster an environment of respect for the dignity and worth of all members of the university community and to eliminate all manifestations of discrimination within the university." Read the full policy.

- UW System: View the UW System policy on the Commitment to Academic Freedom and Freedom of Expression..

- Title IX: "No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance." Learn more on our Title IX webpage.

- Academic Freedom: "Academic freedom includes the freedom to explore all avenues of scholarship, research, and creative expression, and to reach conclusions according to one’s own scholarly discernment."

- Facilities: "It is the policy of the Board of Regents that the facilities of the University are to be used primarily for purposes of fulfilling the mission of teaching, research, and public service. University facilities are not available for unrestricted use for other purposes."

- Political Campaign Guidance: "Political campaign activity includes not only solicitation of campaign contributions, service in furtherance of candidates, political parties and political action committees, and advocating a particular position on a referendum, but also promoting action on issues which have become highly identified as dividing issues between the candidates."

- Expressive Activities: UW-River Falls has a policy regarding Expressive Activity on Campus. This policy describes how UWRF upholds its commitment to free expression while ensuring a safe, respectful campus environment for all.

Our History...and Our Future

The university's establishment in 1874 laid the foundation for a commitment to freedom of expression and academic freedom that would become an integral part of the institution's identity. UWRF is committed to the right of faculty, students and staff to engage in matters of civil discourse and to express their opinions on issues of public interest. This support is underscored by UWRF's dedication to the principles of free inquiry and open debate.

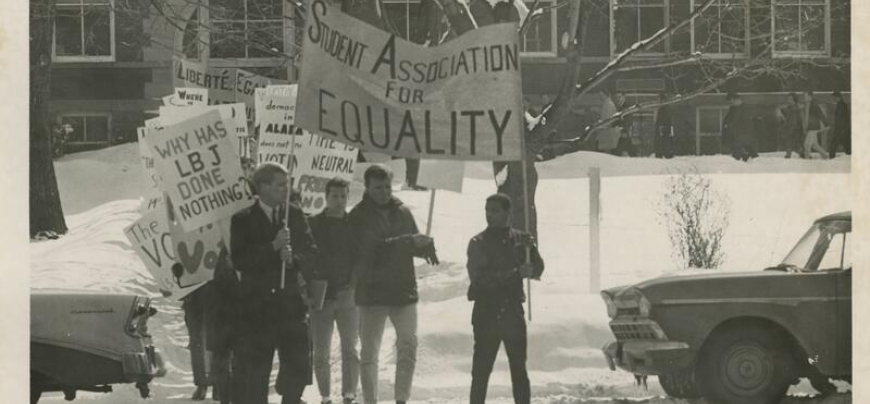

The university's resolve to uphold these principles faced rigorous tests during the McCarthy era of the 1950s and the Civil Rights and Vietnam War era during the '60s and '70s. UWRF, like many other institutions, found itself embroiled in protests and activities that pushed the boundaries of how the concepts of free expression and freedom of speech were understood. In the aftermath of these volatile decades, the university took significant steps to fortify its commitment to the freedom of expression. Bolstered policies not only reaffirmed the rights of all stakeholders, including students, faculty and staff, to express their viewpoints without fear of retaliation but also firmly prohibited any attempts by the university to censor student publications or events.

The evolution of the university's stance on free speech and freedom of expression is a testament to our adaptability and unwavering dedication to our core values. From our inception in the late 19th century to the turbulent '50s, '60s and '70s and the subsequent policy reforms, UWRF has traversed a path marked by both challenges and growth. Today, UWRF stands as a beacon of academic freedom where the exchange of ideas is not only welcomed but fiercely protected. This journey reflects on not just UWRF's commitment to free speech but also resilience in the face of adversity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is there a difference between freedom of speech and freedom of expression?

Freedom of speech is a portion of the First Amendment. The First Amendment, often known as the "Freedom of Expression," protects a wide variety of expressions including: freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and the right to petition the government.

Freedom of speech is not limited to vocalized words or “pure speech." It includes the right not to speak, written speech, symbolic speech (symbols) and speech around conduct (protests). Citation.

What are forms of unprotected speech?

Even though the First Amendment uses the word speech, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that it protects a wide variety of expression. This includes what is known as “pure speech,” meaning the spoken word. The First Amendment also protects expression that is written and expression that is typed and published. It protects symbolic speech or expressive conduct (like burning a flag), and it protects speech plus conduct (like peaceably assembling to engage in protests and boycotts).

There are also a limited number of narrow exceptions to what the First Amendment protects. This includes situations where immediate violence is provoked, someone is unduly intimidated or falsehoods are spread about someone else. They include the following categories:

Incitement to imminent lawless action: There have been instances in U.S. history where the government has attempted to ban speech that people used to advocate for societal change. In some past cases, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld punishment of expression that advocated for change, especially if the speaker called for a revolution or other forms of illegality.

Much broader protection exists for the freedom of expression today. There are exceptions for speech that incites people to violence, but they are very narrow. In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the U.S. Supreme Court held that “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Subsequent Supreme Court cases have clarified that speech advocating illegal action at some indefinite future time is protected by the First Amendment, if it does not constitute criminal conspiracy. These rulings ensure that people can advocate for different forms of societal change, free from government reprisals.

Harassment: Discriminatory harassment is not protected by the First Amendment. As explained by the University of Wisconsin Board of Regents policy document on Discrimination, Harassment, and Retaliation, discriminatory harassment is “unwelcome verbal, written, graphic or physical conduct that: is directed at an individual or group of individuals on the basis of the individual or group of individuals’ actual or perceived protected status … and is sufficiently severe or pervasive so as to interfere with an individual’s employment, education or academic environment or participation in institution programs or activities and creates a working, learning or living environment that a reasonable person would find intimidating, offensive or hostile.” This includes harassment “on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, national origin, ancestry, disability, pregnancy, marital or parental status or any other category protected by law, including physical condition or developmental disability.”

Discriminatory harassment, like incitement, is a narrowly drawn category of unprotected speech. It typically requires repeated activity, as one incident involving speech without conduct is unlikely to constitute discriminatory harassment. As explained by the United States Department of Education, discriminatory harassment “must include something beyond the mere expression of views, words, symbols or thoughts that some person finds offensive.”

Discriminatory harassment is defined in UWRF policy as: Any conduct (verbal, written, physical, etc.) that is directed toward or against a person because of the person’s protected status (e.g., race, gender identity or expression, disability, religion, etc.), and unreasonably interferes with someone’s work, education or participation in programs at UWRF, or creates a working or learning environment that a reasonable person would find threatening or intimidating.

UWRF prohibits sex-based discrimination and will respond to all reports of sexual misconduct as sexual harassment or sexual violence (including assault, dating or domestic violence, stalking and sexual exploitation) with care and support.

True threats: A true threat is not protected by the First Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court defined true threats in Virginia v. Black (2003) as “statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals.” According to the Supreme Court, true threats include when a speaker directs a threat to a person or group of persons with the intent of placing the victim in fear of bodily harm or death.

This definition means that expression that may seem threatening may be protected, as only true threats where the speaker expresses intent to explicitly cause immediate harm are prohibited. An example of seemingly threatening expression that was protected occurred in Watts v. United States (1969), where the Supreme Court overturned Watts’ conviction for stating at an anti-war rally that, “I am not going. If they ever make me carry a rifle the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J.” The Supreme Court ruled that Watts’ language was not a true threat on the life of President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ), as Watts’ rhetoric was simply “political hyperbole.”

Defamation: Defamation occurs if you make a false statement of fact about someone else that harms that person’s reputation. Such speech is not protected by the First Amendment and could result in either criminal or civil liability. Defamation is limited in multiple respects though.

If you make a false statement of fact about a public official or a public figure, more First Amendment protection applies to ensure that people are not afraid to talk about public issues. According to New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), defamation against public officials or public figures also requires that the party making the statement used “actual malice,” meaning the false statement was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

Parodies and satire are protected by the First Amendment (and are not defamatory). Parodies and satire are meant to humorously poke fun at someone or something, not report believable facts.

Obscenity and child pornography: Speech about sex and sexuality receives protection under the First Amendment, and this protection extends to many forms of pornography. However, certain types of sexually explicit expression are not protected.

Obscenity is not protected by the First Amendment. Obscenity is a narrow category of unprotected expression that meets all of the following criteria: (a) the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest; (b) the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.

The government can also restrict minors’ access to pornography, and criminal statutes that prohibit adults from exposing minors to pornography have been ruled constitutional. Additionally, child pornography is not protected by the First Amendment.

Fighting words: The United States Supreme Court ruled in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) that fighting words are not protected by the First Amendment. Fighting words are defined as words “which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” As the Supreme Court explained in Chaplinsky, “[s]uch utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.”

However, the Supreme Court has significantly narrowed the definition of fighting words in recent years and has not upheld a fighting words conviction for several decades. Even if speech is offensive, it is not fighting words if it is not directed to someone face-to-face. There is a question about the continuing validity of the fighting words doctrine at the Supreme Court, although lower courts have sustained some fighting words convictions in recent years.

Non-expressive conduct: Expressive conduct, sometimes called symbolic speech, includes non-verbal activities that convey ideas. For instance, the United States Supreme Court has found protection for wearing an armband with a peace symbol printed on it and for burning the United States flag. Such activities are sufficiently imbued with elements of communication to receive First Amendment protection. Under the same reasoning, protests and boycotts receive constitutional protection.

However, non-expressive conduct receives no First Amendment protection. The Supreme Court has ruled, for instance, that a physical assault of another person is not expressive conduct. Similarly, there is no constitutional protection for protestors who engage in property damage, trespassing, or blocking entrances to buildings.

What is hate speech and is it protected by the First Amendment?

Though there is no legal definition for hate speech, it can be defined as “any form of expression through which speakers intend to vilify, humiliate or incite hatred against a group or a class of persons on the basis of race, religion, skin color, sexual identity, gender identity, ethnicity, disability or national origin.”

Though we acknowledge that hate speech can be hurtful for the recipient, Courts have ruled that restrictions on hate speech would conflict with the First Amendment’s protection of the freedom of expression. Since public universities are bound by the First Amendment, public universities must adhere to these rulings. However, universities also have an obligation to create a safe, inclusive learning environment for all members of the campus community.

With these considerations in mind, courts in the United States have found that expression generally cannot be punished based on its content or viewpoint. Thus, although hate speech, alone, receives constitutional protection, any expression that constitutes a true threat, incitement to imminent lawless action, discriminatory harassment, or defamation can be punished by the government for those reasons, as long as the government does not discriminate on the basis of the content or viewpoint being expressed.

What are time, place and manner restrictions?

Time, place, manner restrictions allow for the regulation of communication and activities in public places. The government is permitted to regulate the time, place, and manner of speech and assembly.

The ruling was first established by the Grayned v. City of Rockford 408 U.S. 104 (1972) Supreme Court Case. “The crucial question is whether the manner of expression is basically incompatible with normal activity of a particular place at a particular time”

Example 1: Individuals can post on certain bulletin boards and pillars on campus, but they are not able to post on every uncovered wall or surface. (See UWRF Sign Posting AP-01-101 for more information on sign posting on campus)

Example 2: Officials may restrict a protest march in a residential neighborhood at 2:00 a.m. in ways it could not restrict the same protest march through a public park at 2:00 p.m.

What am I permitted to post on campus bulletin boards?

UWRF has established bulletin boards on campus, creating in them a limited type of public forum for expression.

Bulletin boards are available on campus for posting. Bulletin boards in academic buildings that are not labeled for a specific department are available for signs promoting university-sponsored or RSO events or groups. Prior approval from a college dean’s office, academic department or administrative office may be needed when posting on bulletin boards that they manage. Those offices are also responsible for the general maintenance and upkeep of the content on their respective bulletin boards.

Signs or posters whose primary purpose promotes any of the following will not be permitted and will be immediately removed:

- consumption of alcoholic beverages

- obscenity

- any violation of university policy

Can I place a lawn sign on campus?

Per UWRF policy, only lawn signs used by Admissions or for the promotion of an official university-sponsored or approved RSO event are allowed. Lawn signs may not be placed in flower beds, next to fire hydrants or impede the flow of traffic. All signs must be placed at least three (3) feet apart and at least three feet from the edge of sidewalks.

Am I allowed to chalk on campus?

Similar to posting flyers on campus bulletin boards, expression through the use of chalking on campus sidewalks is protected within reasonable regulations. Conditions imposed on campus sidewalk chalking are put in place to ensure that permanent damage is not caused to the sidewalks, to ensure the eventual removal of chalk through the weathering process and protect egress paths for entering/exiting buildings and flow of walking traffic.

What is "Heckler's Veto?"

The so-called heckler’s veto — shouting down or drowning out another person who is speaking on campus — is a disruption and is considered misconduct. Read more on state law and policies related to misconduct in Chapter UWS 17 and Chapter UWS 18.

Learn more about the Universities of Wisconsin Commitment to Academic Freedom and Freedom of Expression.

Can I reserve a space for a protest?

Reservable spaces on campus can be reserved by logging into Mazevo with your UWRF account or by contacting reservations@uwrf.edu.

Outdoor locations that are not reserved may be used for protests and student use. The group must not block egress and follow the campus policies, UWS Chapter 18 and UWS Chapter 21

It is the policy of the Board of Regents that the facilities of the university are to be used primarily for purposes of fulfilling the mission of teaching, research, and public service. University facilities are not available for unrestricted use for other purposes. In order to preserve and enhance the primary functions of university facilities, UW-River Falls adopts the following policy to govern facility use on the UWRF campus.

Are people allowed to solicit students?

(8) Selling, peddling and soliciting. No person may sell, peddle or solicit for the sale of goods, services, or contributions on any university lands except in the case of:

(a) Specific permission in advance from a specific university office or the occupant of a university house, apartment, or residence hall for a person engaged in that activity to come to that particular office, house, apartment, or residence hall for that purpose.

(b) Sales by an individual of personal property owned or acquired by the seller primarily for his/her own use pursuant to an allocation of space for that purpose by an authorized university official.

(c) Sales of newspapers and similar printed matter outside university buildings.

(d) Subscription, membership, ticket sales solicitation, fund-raising, selling, and soliciting activities by or under the sponsorship of a university or registered student organization pursuant to a contract with the university for the allocation or rental of space for that purpose.

(e) Admission events in a university building pursuant to contract with the university, and food, beverage or other concessions conducted pursuant to a contract with the university.

(f) Solicitation of political contributions under chapter 11, Stats., and institutional regulations governing time, place and manner.

Dean of Students

Please note: This information is not intended as legal advice.